We automotive journalists can be occasionally prone to a bit of hyperbole when encountering a particularly rare car, often resulting in the liberal use of the word “unicorn”. Sure a 996 GT3 RS is a rare car, the rarest RS of them all, in fact, but with 682 of them built, is it a unicorn? Not quite. However, I don’t think anyone would scoff at the use of the U-word in reference to this mythical beast: a 1-of-17 Ascari Ecosse.

Despite its almost absurd rarity, the Ecosse is a relatively unassuming car at first glance. Sure, it’s incredibly low, but the uncluttered design combined with the unfamiliar badge on the front lend the Ecosse a kit car vibe that it is sorely undeserving of. So, when Neal Heffron invited us to spend some time with his Ecosse, we jumped at the chance to learn more about this unusual machine.

However, before we get into this mighty piece of engineering, it’s worth getting to know its owner. Surrounded by rare cars from a young age — his father owned a Bricklin as a boy — Neal cut his teeth racing behind the wheel of a De Tomaso Pantera which he drove with some success at various track days. Neal had caught the racing bug, and quickly modified his first car — a Ford Fiesta — with a rear wing to enter into increasingly frequent track events.

Eventually, Neal graduated into a full-fledged racer, and once his own business started to perform well, he bought his first Porsche, a 944. This was followed by a 944 S, then a 944 Turbo, and finally a 928, before Neal made the transition to prancing horses. After owning a Ferrari 308 and 328, Neal began competing in the 348 Challenge series, while his love affair with Maranello’s finest would see him purchase a 360 and F430 before finally making the jump to another automotive rarity — a BMW M1 — some 14 years ago. His M1 turned out to be his ticket to the European event circuit, bringing Neal to Villa d’Este, which is where a chance encounter with an Netherlands-based Ascari owner put an Ecosse on his must-own list.

The Dutch enthusiast warned Neal of the car’s scarcity, but to his surprise, that night in his hotel room, he found this exact car in a Bonhams auction listing. The bad news was the auction had ended two days prior, but fortunately the auction winner lacked the funds to take ownership of this Ecosse, and Neal swiftly and happily took his place. However, living in America, Neal was unable to import his new pride and joy, being restricted by the USA’s 25-year import rule. That’s how I found myself standing in front of the ultra-limited run supercar at Classic Concierge in Oxfordshire, accompanied by the car’s enthusiastic caretaker, Mark.

The Ecosse has a distinct prototype racer vibe about it, which speaks to its origins as a track-only racing car called the FGT. The Chevrolet 6.0-litre V8-powered FGT was designed by Lee Noble and made its debut in 1995 at various European motor shows, where it caught the attention of a successful Dutch oil machinery manufacturer Klaas Zwart. Zwart had been considering how to enjoy his considerable wealth at the time, and while a McLaren F1 was an enticing proposition, he decided instead that the money would be better spent acquiring Ascari. Not just a single car, but the whole company.

Zwart, an adept racing driver himself, chose to enter the FGT into the British GT Championship, with just one modular Ford V8-powered FGT homolgated to meet the series' requirements. Against all odds, Zwart won an event at Silverstone Circuit during the car's debut season in 1995, beating some stiff competition, but the rest of the FGT's racing career was less successful.

Following Ascari's brief foray into racing, Zwart decided the FGT deserved a road-going production version. Being ludicrously rich, Zwart didn’t concern himself with profit margins, instead treating his newly acquired company as a tax loss and vanity project; it really was a labour of love. In total, just 17 (or 19, depending on who you ask) examples of the Ecosse left the factory, each of which cost 250,000 pounds to build. This was more than three times the car’s retail price of 80,000, but Zwart was dedicated to building the best car he possibly could, and money wasn’t an object.

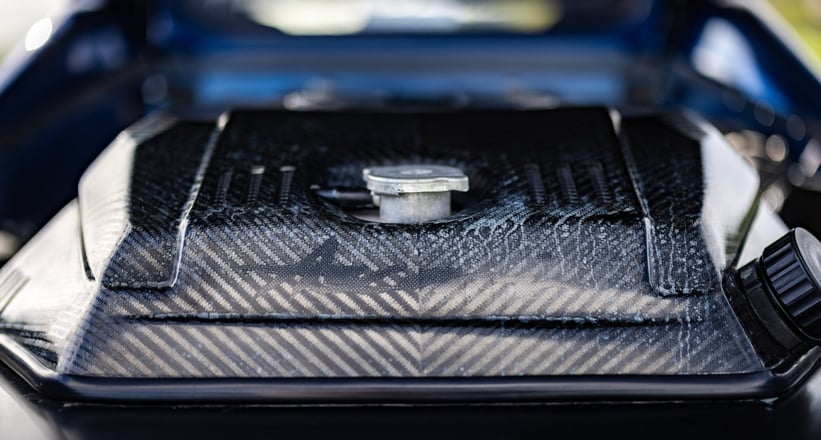

The first examples of the Ecosse were fitted with a 4.4-litre M62 BMW engine putting out around 300 horses, but Ascari learned from each Ecosse they built, and so later models were blessed with a 4.7-litre unit that had been tuned by Hartge to produce closer to 400 horsepower. Being one of the last three built, Neal’s car features an even more developed 4.9-litre Hartge motor pushing out an impressive 420 horsepower, while the real point of intrigue is its gearbox: a Quaife sequential transmission.

Sitting in the Ecosse’s rather cosy cabin, one can immediately sense the surprisingly great build quality, which is exactly the opposite of what you’d expect from a company’s very first road car. Nevertheless, the Ascari’s simplistic yet solid cabin is a comfortable, if a little cramped, place to be, once you’ve managed to traverse the car’s particularly wide door sills. Sitting right up against the front axle, your feet feel as though they’re kicking the back of the Ecosse’s numberplate, while the wing mirrors offer an excellent view of the Ecosse’s elongated tail and XJR 15-esque rear wing. The sequential gearbox is admittedly not the first choice for crawling through Oxfordshire’s tightly packed villages, but the BMW V8’s ample torque means third gear is as low as you need to go for most slow-speed driving.

Having spent a good portion of the summer in the driver’s seat of his newly-acquired Ascari, Neal was pleasantly surprised by the car’s good manners. “It’s got the best of all world’s, it’s very torque-y, it has a big BMW V8, but it’s quite reliable. It’s a supercar, but it was built like a GT, despite the fact it’s a race car that was converted into a street car. Visibility is great, which you wouldn’t expect, and the view from the front is amazing; you see straight down into the pavement. It has a very wide turning circle, and your feet are pushed towards the middle of the car, but everything else is fairly standard, and switchgear and gauges are all normal.”

As I quickly discovered, it’s also surprisingly supple for a supercar, and Neal was quick to confirm: "It’s very compliant: it’s very low but it has enough clearance so it really doesn’t have many issues around town. It’s all analogue, so there aren’t any electronic nannies — no ABS and no traction control — it’s a real driver’s car.”

Neal, who also owns a Carrera GT, also mentioned how impressed he was with the car’s build quality, and I have to concur. The entire body is made from carbon kevlar, and yet you won’t catch a single sign of the composite weave beneath this Ecosse’s BMW Avus Blue paintwork. “It has AP brakes. They basically took all the best performance parts off the shelf at the time,” Neal tells. “The whole engine compartment is aerodynamically sealed, including the bottom, yet there are fans in the engine bay, so the car never gets too hot. The previous owner also never had any electrical issues, and Ascari made their own wiring loom in house to military spec with aircraft connectors,” he continued, further highlighting the Ecosse’s surprising level of fit and finish. “It’s not a kit car, it’s a real high-end production car built to compete with the Ferraris of the era.” Neal concludes, and having thoroughly enjoyed blasting around Oxfordshire in the Ecosse, I’d agree: this really is just as tantalising as any early-2000s prancing horse, and arguably even better built.

Photos by Mikey Snelgar